Flavor is the sensory impression of food or other substances, determined primarily by the chemical senses of taste and smell. It is the nuanced blend of taste and aroma that creates the full experience of flavor in our minds. Unlike taste, which is limited to five basic categories, flavor encompasses a broader spectrum, including the aromatic compounds that evoke smell. This complex interaction not only allows us to discern what we eat and drink but also plays a crucial role in our enjoyment and preference for certain foods and beverages. In essence, flavor is the gateway to our culinary world, influencing our eating habits and shaping our cultural and individual identities.

How do humans perceive flavor?

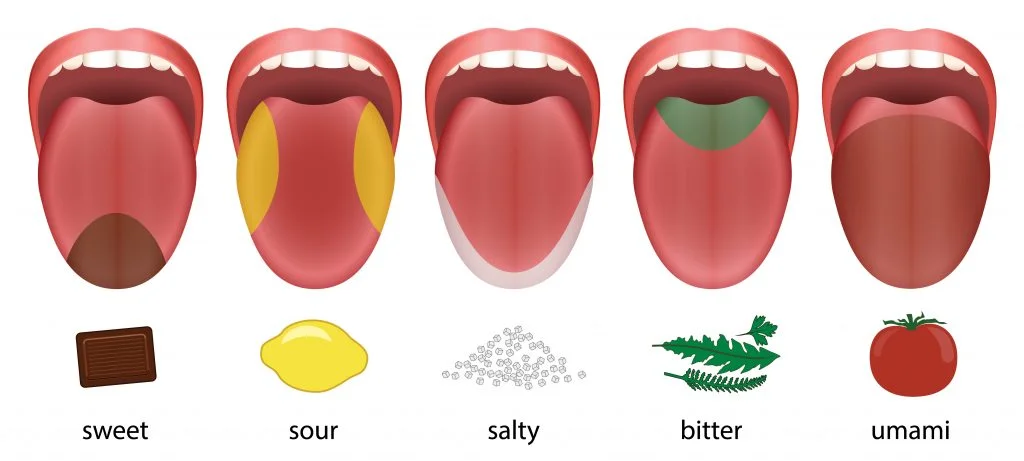

Humans perceive flavor through a sophisticated interplay between taste and smell, utilizing taste buds on the tongue and olfactory receptors in the nose. Taste buds are responsible for detecting the five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami, each linked to specific dietary needs or warnings. Meanwhile, olfactory receptors capture aroma compounds, which, when volatilized, provide the nuanced and complex dimensions of flavor beyond basic tastes. This dual pathway allows for a comprehensive perception of flavor, integrating both gustatory (taste) and olfactory (smell) information to create the rich experience of flavor that guides our food preferences and consumption behaviors.

Through taste buds on the tongue

Taste buds on the tongue are specialized sensory cells that detect the five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. Each taste is associated with specific dietary needs or serves as a warning for potential toxins. These receptors send signals directly to the brain, allowing us to identify and differentiate flavors based on their taste profiles.

Through olfactory receptors in the nose

Olfactory receptors in the nose play a crucial role in flavor perception by detecting aroma compounds. These receptors capture the volatile molecules released by food, which contribute to the complexity and nuance of flavors beyond the basic tastes. The integration of olfactory information with taste signals creates the full experience of flavor, highlighting the importance of smell in our perception of food and drink.

What are the primary tastes?

The primary tastes, fundamental to human perception of flavor, consist of sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. Sweet taste is often linked to energy-rich foods, signaling the presence of sugars. Sour taste typically indicates acidity, a characteristic of fermented or spoiled foods, yet also found in fresh fruits. Salty taste is essential for maintaining bodily function, indicating the presence of minerals. Bitter taste, often a sign of toxins, serves as a natural deterrent, though it is also found in many beneficial foods. Lastly, umami, recognized as the taste of proteins and amino acids, signifies the presence of savory flavors. Together, these tastes help navigate the nutritional landscape, guiding dietary choices and preferences.

Sweet: often associated with energy-rich foods

The sweet taste is primarily linked to the presence of sugars in foods, serving as an indicator of energy-rich options. This taste preference can drive the consumption of fruits, certain vegetables, and honey, providing essential calories for bodily functions.

Sour: typically indicates acidity

Sour taste is a marker of acidity, found in citrus fruits, fermented products, and foods that may be spoiling. It plays a critical role in the culinary world, adding depth and balance to dishes, while also signaling the freshness or potential spoilage of foods.

Salty: essential for maintaining bodily function

Salty taste is vital for indicating the presence of essential minerals, such as sodium, which are crucial for maintaining bodily hydration and electrolyte balance. This taste preference encourages the consumption of foods necessary for survival.

Bitter: often a sign of toxins

The bitter taste can serve as a natural warning system against the consumption of toxic substances. Despite its association with potential danger, many beneficial and nutritious foods also possess a bitter taste, which can be acquired and appreciated over time.

Umami: signifies proteins and amino acids

Umami, often described as savory, is the taste associated with proteins and amino acids, found in meat, cheese, mushrooms, and certain vegetables. It is a relatively recent addition to the list of primary tastes, highlighting the complexity and richness of flavors that signal nutritional content.

How does smell contribute to flavor?

Smell significantly enhances the perception of flavor through the detection of aroma compounds by olfactory receptors in the nose. When food is consumed, these volatile compounds are released and travel to the olfactory receptors, adding depth and complexity to the basic tastes identified by the taste buds. This interaction between taste and smell creates a combined perception of flavor, making the experience of eating and drinking much more nuanced and enjoyable. The role of smell is so pivotal that without it, our ability to discern the full range of flavors in food would be markedly diminished, underscoring the intricate relationship between olfaction and gustation in flavor perception.

Aroma compounds volatilize and reach the olfactory receptors

Aroma compounds in food volatilize, or turn into gas, during the process of eating, heating, or cooking. These volatile molecules then travel through the air and reach the olfactory receptors in the nose. This interaction is crucial for detecting the wide array of smells that contribute to the overall flavor experience, highlighting the importance of aroma in the perception of food and beverages.

Interaction with taste creates a combined perception of flavor

The interaction between the sense of taste and smell leads to a combined perception of flavor that is far more complex and nuanced than either sense could achieve alone. Taste buds detect basic tastes like sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami, while olfactory receptors pick up on the vast spectrum of aromatic compounds. Together, they form a comprehensive flavor profile, enabling us to enjoy and discern the flavors in our food and drinks with remarkable depth and precision.

What factors influence flavor perception?

Flavor perception is not solely a direct result of the chemical components of food and drink but is also significantly influenced by a variety of external and internal factors. Age plays a critical role, as taste sensitivity tends to decrease over time, altering how flavors are experienced. Genetics also have a profound impact, with variations in taste receptor genes affecting sensitivity to certain tastes. Health conditions can modify taste and smell, sometimes temporarily or permanently changing one’s flavor perception. Additionally, the environment in which food is consumed, including ambiance and social settings, can affect how flavors are perceived. Collectively, these factors underscore the complexity of flavor perception, illustrating that it is a deeply personal experience shaped by both biological and environmental influences.

Age: taste sensitivity decreases over time

As individuals age, their taste sensitivity tends to decline, leading to changes in how flavors are perceived. This decrease can affect the intensity and enjoyment of certain foods and beverages, altering dietary preferences over time.

Genetics: variations affect taste receptor sensitivity

Genetic variations play a significant role in determining the sensitivity of taste receptors. These genetic differences can explain why some people have a heightened sensitivity to tastes such as bitterness or sweetness, influencing their food preferences and flavor experiences.

Health: certain conditions can alter taste and smell

Various health conditions, including illnesses and medications, can temporarily or permanently alter an individual’s ability to taste and smell. These changes can significantly impact flavor perception, affecting appetite and enjoyment of food.

Environment: ambiance can affect flavor perception

The environment in which food is consumed, including the ambiance, setting, and even social context, can influence how flavors are perceived. Factors such as lighting, noise, and company can enhance or diminish the overall experience of flavor, highlighting the role of external influences on taste.

How do cultural differences affect flavor preferences?

Cultural differences profoundly shape flavor preferences through the influence of regional ingredients and traditional cooking methods. Local availability of ingredients dictates the base flavors of a region’s cuisine, leading to a diverse palate across different cultures. For instance, the prominence of spices in South Asian cooking contrasts with the subtler flavors preferred in many European dishes. Traditional cooking methods, passed down through generations, also play a crucial role in defining the flavor profiles unique to each culture. These methods, whether it involves fermentation, smoking, or the use of specific cooking utensils, contribute to the distinctive tastes that are cherished and preserved within communities. Consequently, cultural heritage and practices are pivotal in shaping not only individual flavor preferences but also the broader culinary landscape.

Regional ingredients: local availability shapes taste

The availability of regional ingredients significantly influences the development of distinct flavor profiles within a culture’s cuisine. Geographic and climatic conditions dictate the types of crops that can be grown and the animals that can be reared, directly affecting the tastes that become foundational to a region’s culinary identity. This local availability not only shapes the ingredients used in cooking but also influences dietary habits and preferences over generations.

Traditional cooking methods: historical techniques influence flavor

Traditional cooking methods, deeply rooted in history and culture, play a pivotal role in defining the unique flavors of a cuisine. Techniques such as fermentation, smoking, steaming, and grilling, passed down through generations, impart specific tastes and textures to food. These historical methods are often closely tied to the available resources and technologies of a region, reflecting the ingenuity and culinary heritage of a community. The preservation of these methods ensures the continuation of rich, diverse flavor profiles that are characteristic of different cultures around the world.

Flavor in Whiskey Production

In whiskey production, flavor is not merely a byproduct but the essence of the craft, meticulously shaped at every stage of the process. From the selection of grains to the intricacies of fermentation, distillation, and aging, each step contributes uniquely to the whiskey’s final flavor profile. The choice of grains introduces the foundational flavors, while fermentation adds complexity through the creation of various alcohols and esters. Distillation concentrates these flavors, and aging in wooden barrels infuses the whiskey with additional character, including notes of vanilla, caramel, and oak. The type of barrel, the environment in which it’s stored, and the duration of aging further influence the whiskey’s taste, aroma, and color, culminating in a beverage that is as rich in flavor as it is in history and tradition. This intricate interplay of factors ensures that each whiskey is a unique expression of its ingredients and the conditions under which it was produced, offering a diverse spectrum of flavor experiences for connoisseurs to explore.

How does the production process influence whiskey’s flavor?

The production process plays a pivotal role in shaping whiskey’s flavor, with each step from grain selection to aging contributing distinct characteristics. Grain selection sets the foundational flavor, determining the primary notes that will be developed through subsequent processes. Fermentation introduces complexity, as yeast converts sugars into alcohol and other compounds, adding fruity, floral, or spicy notes. Distillation further refines these flavors, concentrating the alcohol and flavor compounds, while removing undesirable elements. The most transformative stage, aging, occurs as the whiskey matures in wooden barrels, often oak, which imparts rich flavors of vanilla, caramel, and wood spice. The type of wood, the barrel’s history (e.g., new, charred, or previously used for other spirits), and the aging environment (temperature, humidity) significantly influence the final flavor profile. Through this intricate process, whiskey develops its unique and complex flavors, making each batch a distinct expression of its production journey.

What are the common flavor profiles of whiskey?

Whiskey’s flavor profiles are as diverse as they are complex, ranging from light and floral to rich and smoky. Lighter whiskeys often feature fresh, grassy notes and a gentle sweetness, making them approachable and versatile. On the other end of the spectrum, rich whiskeys boast deep flavors of vanilla, caramel, and oak, derived from extended aging in charred barrels. Smoky whiskeys, particularly those from regions like Islay, are known for their peaty character, offering earthy and medicinal notes that are highly prized by enthusiasts. Spicy whiskeys reveal warm notes of cinnamon, pepper, and nutmeg, often influenced by the grain blend or the barrel’s previous contents. Lastly, fruity and floral whiskeys present with delicate aromas of apple, pear, and spring flowers, a reflection of careful distillation and maturation processes. Each whiskey’s flavor profile is a testament to its ingredients, production process, and aging, inviting a journey of discovery with every sip.